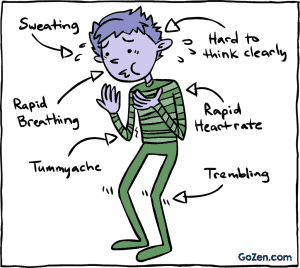

Sherri was 11 years old and woke up most mornings complaining her tummy ached and had trouble eating her breakfast. Her foster father Mike noticed that every time they would drive to her visitations with her bio mom, she would rub her head and seemed to have a hard time concentrating on conversation. Her behavior would accelerate a few days before these visits: outbursts, magnified fears, her hands always seemed to be clammy, she would often complain about feeling cold and Sherri often seemed disorganized in her thoughts. Mike repeatedly told her she was okay and did his best to reassure her but nothing seemed to really help. Sherri’s anxiety was interfering with every part of her life and that of her families as well.

For kids like Sherri, these symptoms are not uncommon. Children and youth that have a history of complex trauma, often have an over-reactive stress response. Simply put, their brains are always ‘on’. I want to share a parallel example to provide context for this. I lived in S.E. Asia for 10 years and we had massive, winged cockroaches that would fly into our house and somehow squirm their way up our drains. I want you to imagine that you are terrified of these bugs (like I am). One day, when you start running the bath for your toddler, one of these winged creatures crawls out of the drain and flies right at you, getting stuck in your hair. You scream. You bat your hair and you frantically jump up and down like a crazy person. The cockroach flies away but you, you are a hot, sweaty mess with a racing heartbeat and your adrenaline is racing. Most of us after a few minutes, regulate our emotions and our hyper-arousal state calms down. However, for kids living with the residual impact of complex trauma, this type of hyper-arousal is innate within them and they don’t know how to ‘calm’ down. This is their normal and it has been their protective defense system (flight, fight or freeze) for many years.

In our CCI (Complex Care & Intervention) training manual, Dr. Chuck shares that the brain and nervous system form neural pathways during the early developmental years of life which act as key building blocks for all of our neural signaling and “when an environment is unstable and unsafe because it is impacted by violence, chaos and flooded with stress hormones, the child adapts by becoming hypersensitive to outside sounds and sensations, and remains in a persistent stress-response state (Perry,1994a: Perry, 1995a).” This means that the child’s autonomic functioning is hyper-sensitized and thus, the observable physiological symptoms that Sherri and many others live with every day.

Dr. Chuck et al continues, “Children experiencing maltreatment learn to continually scan their environments and relationships for clues to their safety (Zilberstein, 2014). In the event that relationships have proven perpetually unsafe, children remain in a heightened state of emotional arousal even if they look calm. They scan their environment for the slightest suggestion of danger. For many, even the most benign relational gestures are interpreted as threats”.

As parents, when we perceive our children are anxious, we want to help. In our efforts at well-meaning, we tend to adopt some of following techniques: reasoning with our child about all the reasons why they shouldn’t feel anxious or upset, repeatedly telling them they are okay, encouraging them to just step into their fears and ‘do it’ and/or getting frustrated ourselves because of the amount of energy and patience we are exerting into them but with no impact.

Anxiety is overwhelming; it’s difficult for the child and it can be a difficult thing for caregivers or even take it’s toll on a whole family. So, what can we do and how do we apply a trauma-centric approach so that we can aide our child/youth in self-regulation and aim for CALM.

Anxiety can be overwhelming for both the child and the caregiver so here are a few tips on what you can say and do to help your child/youth:

- Develop emotional literacy – help your child understand the names of emotions. So for example, if they are presenting with anxiety about something specific, you can say, “Kai, I notice that your heart is beating really fast right now and I wonder if you might be feeling…(insert: nervous, scared, upset, worried, etc.) about….(insert: name what this might be). As the child develops an understanding around this kind of language, you could move into prompting them and helping them self-identify what they are feeling. Giving anxiety specific names helps to calm the dragon inside.

- Assure them they are not alone in that moment and that you understand. You could say something like this, “I know what that this feels like. When I feel like this (insert: name feeling) it makes my tummy do flip flops and it makes my heart beat really quickly.

- Sometimes assuring them that worry is okay can be helpful. Help them understand that worry is like a thermometer that tells our bodies certain messages. If we get too hot or too cold, we need to listen to our bodies and take action.

- Cultivate mindfulness as a daily exercise. Incorporate mindfulness activities that the child can either do with you or on their own to teach them self-regulation. e. grounding, deep breathing, utilizing calming tools etc.

- Have a calming box in your home and fill it with special ‘tools’. I’ve done this with my daughter and recently she packed one all by herself for one of her dance competitions. She filled it with: play-dough, a stress ball, essential oils, slime, her iPod to play calming music/earphones. You could add a balloon to help regulate breathing, a rubbing stone, a special blanket, some feeling cards, jokes on hand to help them laugh etc.

- Break the worry down into bite size pieces. Often anxieties feel larger than life so breaking them down into manageable bits can be very helpful. For example, if a child that is scared of going to sleep at night typically starts to act up after dinner time, a caregiver could: 1. Identify the fear. 2. Walk through what will happen each step of their predictable routine leading to the ‘actual bedtime’ (First things first) 3. Keep to a predictable routine – provides continuity and safety for child which is extremely important if there has been significant chaos or abuse at this time. Lots of hugs and reassurance. 5. Calming routines before bed: combing hair, reading books, deep breathing exercises, sound machine etc.

- Read books together about ‘anxiety’ or ‘worry’. Often authors will create special characters that can be translated into everyday life. Here is a list of various books that are age specific which Living the Life Fantastic has accumulated as a reference for you: https://www.livingthelifefantastic.com/2013/10/31-days-to-peace-day-15-helping-children-with-anxiety-13-recommended-books/

- Help direct them to a time when they faced the same feelings and were able to overcome. Strengthening their ability to resolve past fears/worries will help them to build into a new ‘experience bank’ that they are able to pull dividends from in the present moment.

- As the caregiver, modeling peaceful and calming strategies will be a great source of strength to the child. Ask them to copy what you are doing and watch how their somatic symptoms tangibly shift. For example: have child feel their racing heart then after you have done some deep breathing, have them feel how their heart has slowed down.

None of this is a quick fix, however, we have found that over time, developing calming strategies, building new experiences and modeling calm and assurance for your child will help to actively assist in resetting their autonomic nervous system and over time, these positive experiences will help to create new neural pathways. These are positive outcomes that enable a child to learn better self-regulation skills, enhance attachment (as the primary caregiver is a crucial element in walking this journey with the child) and also often assists with behavioral regulation.

Please Note: Nicole works part-time as a Complex Care and Intervention coach for Complex Trauma Resources and these have been re-printed by permission from Complex Trauma Resources Ltd. ©